Wildlife scavenging at the intersection of aquatic and forested habitats: a tiny morsel goes along way

December 18, 2017

Writer: Vicky L. Sutton-Jackson, 803-725-2752, vsuttonj@srel.uga.edu

Contact: Erin Abernethy, 803-617-9589, efabernethy@gmail.com, Olin E. Rhodes, Jr,

803-725-8191, rhodes@srel.uga.edu

In a landscape of wetlands and forested habitat, scientists at the University of Georgia’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory found that vertebrates are giving insects a bit of competition for a nutritious meal.

Their study results, reported in the November issue of Ecosphere, indicate that ants and beetles—scavenged about 80 percent of the carcasses of reptiles and amphibians.

By comparison, vertebrates including raccoons, opossums, rats, snakes and birds lagged behind—scavenging 19 percent of carcasses.

Although many reptiles and amphibians inhabit the wetlands found in the Southeastern U.S., previous studies report a low percentage return to these wetlands to breed, therefore the researchers conclude that many perish, turning into small morsels of nutrition at the intersection of forest and water.

The researchers placed cameras in two habitats in South Carolina: a wetland, and an upland forested habitat. The cameras captured the consumption of 200 carcasses.

Erin Abernethy, lead investigator, and alumna of SREL and the Odum School of Ecology, said the team anticipated that invertebrates would consume the majority of the carcasses because bugs are always on the landscape. They are fast and able to get a head start, but the researchers were slightly surprised by the study results.

“We anticipated that invertebrates would quickly get to a carcass and scavenge most of the flesh before a vertebrate walked by,” said Abernethy, who is now at Oregon State University. “What was surprising, was that in the short time span before invertebrates decimated carcasses, usually less than two days, some raccoons were able to find these tiny carcasses and utilize them as a food resource. Prior to this study, we didn’t know how these really tiny packets of energy were utilized as a food source.”

Abernethy said the results are reason to be concerned. If global population declines continue due to disease and climate changes, that could impact other species higher in the food web.

Olin E. Rhodes, Jr., Abernethy’s advisor on the study, director at SREL and a professor at the Odum School, explained “If, upon death, amphibians and reptiles are routinely consumed as sources of nutrients for other species, this has important consequences to our understanding of both how species depend upon amphibians and reptile carrion to survive as well as how contaminants move from aquatic to terrestrial environments through scavenging,” he said.

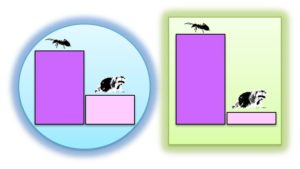

Habitat was the factor influencing overall scavenging success, or which group, the vertebrates or the invertebrates, scavenged the most carcasses.

James Beasley, team member and assistant professor at SREL and the Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, explained that vertebrates are more successful near wetlands because mid-sized carnivores, like raccoons and opossums, spend considerable time near wetlands, where they prey on reptiles and amphibians. “This was evidenced in our data where vertebrate scavenging success was 2.5 times higher along wetland edges compared to our trials in upland terrestrial areas,” he said.

The full study, Scavenging along an ecological interface: utilization of amphibian and reptile carcasses around isolated wetlands, can be found at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ecs2.1989/full

Kelsey Turner is an additional author on the study, SREL and Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia.

###