The Power of Progress: Head-starting and the Future of Mojave Desert Tortoise Conservation

By Lauren Maynor

Researchers from the University of Georgia’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory in collaboration with the University of California, Davis, recently conducted a study in the Mojave National Preserve in San Bernardino County, California, to further investigate the effectiveness of head-starting as a conservation tool for the Mojave desert tortoise. This species is currently listed as “Threatened” under the federal Endangered Species Act due to significant threats from habitat destruction and over-exploitation and was listed as “Endangered” by the State of California. Because of their slow life histories, tortoises are particularly vulnerable to population declines, making it imperative to find innovative conservation solutions.

Tracey Tuberville, senior research scientist at UGA’s SREL and one of the lead scientists for this project, states, “The main reason that the Mojave desert tortoise is threatened stems from human alteration or destruction of its habitat. Increased drought and wildfires can also cause direct mortality of these desert-adapted animals.”

Head-starting involves the raising of juveniles to larger sizes to improve their survival and protect them during their vulnerable early life stages. While head-starting doesn’t fix the problems that originally led to the decline of desert tortoises, it can help “jump-start” populations by injecting a pipeline of juvenile tortoises that have made it past the most vulnerable years of their life.

“Some populations have declined to an extent that they are unlikely to recover on their own,” Tuberville explains. “By helping animals through those vulnerable first few years, we are increasing the number that are on the trajectory to adulthood. There is also a good chance that head-starting might also shorten the time it takes juveniles to reach adulthood because maturity is based on size, not age.”

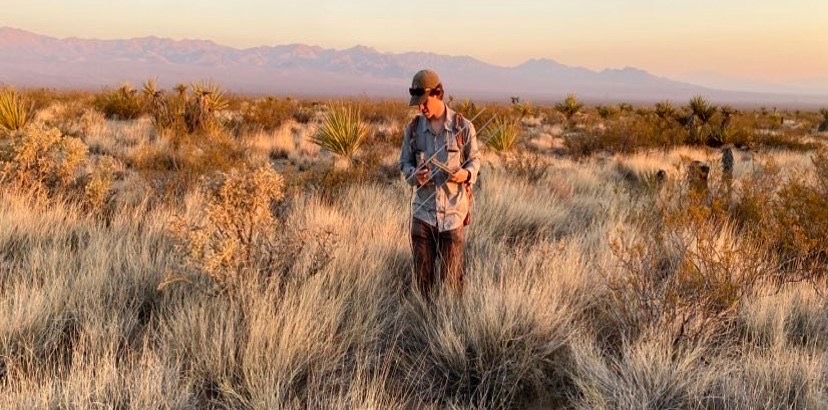

In the recent study authored by SREL graduate student Collin Richter, researchers attached radio transmitters to released tortoises to track their movements and monitor survival. For three years researchers periodically recorded each tortoise’s location and behavior. The tortoises were released in the Mojave National Preserve as part of the long-term effort by SREL, UC Davis, and the National Park Service to help recover desert tortoise populations in the park.

They found that a tortoise’s space use depended on the head-starting treatment that it received. Smaller and younger tortoises had smaller home ranges and higher site fidelity, which is the tendency of an animal to return to a previously visited location. However, regardless of how tortoises were head-started, their home range size decreased, and site fidelity increased with time since release, indicating that they had settled into the release site.

Their study yielded rare and valuable insights into juvenile Mojave Desert tortoise behavior and head-starting as a tool for tortoise conservation. The study found that survival rates did not differ significantly among the three treatment groups or with tortoise age or size. Survival for all treatment groups was high, except in the final year of monitoring when tortoises had to battle extreme drought conditions.

“Sometimes things happen that are beyond our control, such as drought after a release year,” Tuberville explained. “One of our most successful programs has been for desert tortoises. We knew from the outset that it would be a twelve-or-more-year project. That allowed us the ability to try different rearing and release methods, experimentally test them, and compare the results. And progress has been incremental, with us learning from each release and continually trying to optimize or improve the process.” The study is the latest in a series of efforts by the researchers and their graduate students to help develop tools for recovering turtle populations.

Head-starting has been viewed with skepticism because it is often difficult to evaluate and some question its effectiveness at increasing populations. However, head-starting has shown promise for many species, especially when used in unison with other conservation measures that target multiple life stages. Attitudes have certainly changed over the past two decades and practitioners have been more open-minded towards head-starting. This change of heart is partially due to the increasing concerns for turtle species and that more intrusive management may be necessary to recover their populations.

Tuberville explains, “One type of criticism has been that head-starting is a ‘bandaid’ that doesn’t fix the root of the problem. We’ve never approached head-starting as a way to compensate for the loss of adults from the population. Rather, we’ve viewed it as one tool to use in concert with other management options.”

There are a growing number of studies that have been conducted on post-release monitoring of a wide variety of head-started turtle species. Many of these scientific studies had promising results. This provides the leverage or assurances that some practitioners or agencies are seeking before they implement head-starting themselves.

The future of Mojave desert tortoise conservation is promising now that SREL researchers feel like they have an efficient head-starting method that works well for desert tortoises. They are looking for novel ways to use these head-started tortoises to recover their populations.

“We hope that by making it efficient and cost-effective, head-starting might be implemented at more sites across the species’ range,” Tuberville states. “Current angles we are exploring include restoring sites after wildfires or releasing at sites that may serve as climate refugia.”

Climate refugia is an area where special environmental circumstances have enabled a species to survive after failure to survive in surrounding areas.

Results of the study were published in the journal Global Ecology and Conservation, titled Effects of head-starting on multi-year space use and survival of an at-risk tortoise, completed by Collin Richter, Brian Todd, Kurt Buhlmann, Carmen Candal, Pearson McGovern, Michel Kohl, and Tracey Tuberville.