The case for reintegrating ecosystem science into the discipline of radioecology

Behind the myriad of global concerns currently at the forefront for mankind, lies the reality for scientists that radiological contaminants have increased globally. Stark evidence is provided by the abandoned cities forever changed in Chernobyl and Fukushima as a result of nuclear fallout and the billions of dollars spent on the cleanup of legacy waste from nuclear production sites.

A few years ago, 60 scientists convened at the University of Georgia’s Conference Center near Aiken to evaluate the need and rationale for reconnecting radiation protection programs with ecosystem science.

They represented the Association of Ecosystem Research Centers, the International Union of Radioecology, and staff from the UGA’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory. Experts in their field, they brought two undeniable advantages to the discussion table—diversity and objectivity.

The group was composed of individuals from the United States, Russia, and Asia. Among them were statisticians, health physicists, ecotoxicologists, geneticists, and wildlife ecologists, as well as individuals trained in the fields of ecosystem science and radioecology.

For the first time, many of these individuals were asked to assess the field of radiation protection and if ecosystem science should be connected to radiological risk assessments.

The three-day symposium proved prolific, like the research conducted by the late Dr. Eugene Odum 70 years ago tracing radionuclides through ecosystems on the very same landscape.

It became exceedingly clear to these experts that radiation programs have lost the needed connection to the protection of natural ecosystems. Yet, the link between ecosystems and human health cannot be denied.

The 60-person group came to a consensus that it is vital to reconnect radiation protection programs to ecosystem science to facilitate the protection and monitoring of the plants, animals, and microbes that provide critical ecosystem services to humans and organisms. Services like clean air and water, the production of food and fiber, regulating climate and diseases, and nutrient cycling.

Ultimately, human protection depends upon protection of our environment. To miss this connection is to put the health of all humanity in danger and ecological education on weak footing. Decision makers must acknowledge this link and protect educational programs that produce future generations of scientists with proper training in nuclear science as well as ecology.

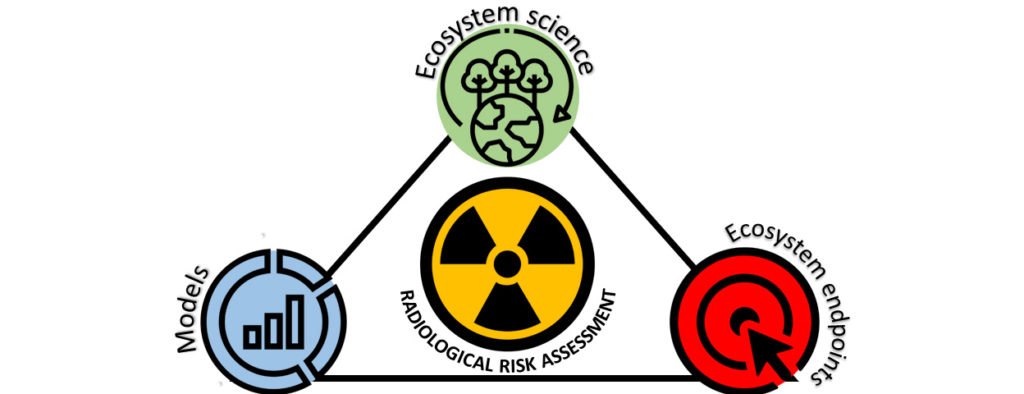

The scientists developed solid recommendations after addressing a series of questions, including: How can ecosystem science support ecological risk assessments?

Their recommendations are published in “Integration of ecosystem science into radioecology: A consensus perspective.” The study appears in this week’s edition of the highly reputable journal, Science of the Total Environment.

The following is a summary of the recommendations:

- Ecosystem science has matured to the point where its theoretical foundation and scientific methods can support radiological risk assessments that utilize ecosystem-level measurements.

- The same ecosystem measurements that are used to assess the risk from contaminants such as heavy metals and pesticides can be used for risk assessments conducted for radionuclides.

- Any risk assessments for measurement of radiological risk must be built upon sound statistical frameworks and conceptual models.

With this clarity of linkage and need, one might ask how did the study of radioecology lose its foundation or connection to ecology?

This occurred for numerous reasons, including the implementation of essential environmental protection regulations designed to protect ecosystems and a shift to programs primarily focused on human protection from direct exposure to or consumption of radioactive elements, known as radionuclides.

The transition mirrors our timeline through nuclear history. Understandably, like a train that changes tracks, we moved from Cold War concerns that began in the 1950s to dismay at the devastating human loss caused by the accidents in both Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima in 2011.

But we must move forward with a bird’s eye view and with gained insight from Odum, the father of modern ecology. Again, this exigency is upon us, as the use of nuclear materials has not ceased. Nuclear materials continue to be used around the world to produce energy, weapons, and fuel. We cannot afford missed opportunities and second guesses—the cost is too high.